Bringing academia and industry together

Each year, the National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB) celebrates universities and industry working together to improve prosperity and innovation. This year’s report highlights the contributions from two SES members, the University of Oxford and Imperial College London.

As 2021 comes to a close, the annual National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB) State of the Relationship report has been released, highlighting collaborations between academia and industry across different universities.

The report includes a “collaboration progress monitor” which examines the links between universities and business, looking at skills, talent, research and innovation. Despite the disruption of the pandemic, which led to an overall decline in the total number of interactions between universities and businesses in 2019/20 compared to 2018/19, many indicators still equalled or outperformed the five-year average.

Two SES member universities have been commended in the report for their focus on world-leading innovation as well as building strong relationships with growing industries.

Spinning in at Imperial College London

The concept of a spin-out is broadly understood, where a company has been grown out of a university’s research. But at Imperial College London, spin-ins are also forming part of its tech transfer and knowledge exchange approaches.

A spin-in is where an outside company benefits from university inventions, research, technologies and facilities. This is often done in return for an equity stake and/or a mix of licensing royalties and research funding, so it becomes part of a university’s commercialisation strategy.

Dr Rebeca Santamaria-Fernandez, director of industry partnerships and commercialisation – engineering, enterprise, says: “It is increasingly the case that external start-ups and SMEs from outside the Imperial innovation ecosystem seek engagement with our tech transfer office to commercialise existing inventions.

“This approach… diversifies routes to impact and leverages expertise, talent and facilities, whilst assisting existing start-ups and SMEs. It’s an attractive proposition.”

Imperial uses criteria to ensure spin-in opportunities are the right fit. This includes making sure there’s alignment with the key research and impact objectives of the college and that there are opportunities for collaborative research with Imperial’s inventors.

Several partnerships are already in place across different industries. Ariel AI was founded in 2018 and in 2020 it licensed intellectual property from Imperial in return for equity. The company uses computer vision to build augmented reality features, and it was recently acquired by Snap Inc., the parent company of social media app Snapchat.

In the MedTech sector, a number of companies are currently benefiting from a ‘spin-in’ relationship with Imperial – for example: a young SME that supplies instrumentation for studying molecular and cellular binding mechanisms, a US-based premarket company specialising in nephrology health but looking to expand into gut health, and a new start-up from a leading US university developing an advanced therapeutics platform. All three businesses are benefiting from collaboration with researchers, allowing innovations to impact patients more rapidly.

‘Creative destruction’ at the University of Oxford

Beginning in 2012, the Creative Destruction Lab (CDL) is an objective-based mentoring programme for scalable, seed-stage, science and deep-tech ventures. The non-profit’s aim is to guide companies to commercialisation, taking no fees to ensure maximum uptake.

The University of Oxford launched their branch of the global CDL network in Autumn 2019. Based at Oxford Saïd Business School, CDL-Oxford is the first CDL site in Europe, harnessing the convening power of the university to bring together a community of mentors, scientists and postgraduate business students. Its first Artificial Intelligence cohort was so successful that the programme was soon expanded.

In 2021, CDL-Oxford ran four streams covering AI, Climate, FinTech and Health. Over 130 mentors committed their time to guide 80 ventures and 100 University of Oxford MBA and postgraduate students.

Covid-19 recovery with Oxford Life Sciences

Business partnerships have been crucial to Oxford’s life sciences research and innovation for many years. But when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, these relationships became vitally important in the global effort to produce a vaccine.

Oxford’s scientists in the Jenner Institute and Oxford Vaccine Group had already developed the vaccine platform, and a link with AstraZeneca was already in place, but not well established. However, this partnership has shown how agile thinking and action can move projects along at much greater speed, without compromise.

In just 10 months, the collaboration achieved what would normally have taken 10 years by normal R&D standards. This was down to strong teamwork and clear, shared goals from the beginning. A joint sense of urgency and trust allowed all the steps to happen in parallel – clinical trials were organised, manufacturing was organised, contracts were drafted, and partners were approached together.

Although the circumstances were extraordinary, industry partnerships will be integral to the establishment of Oxford’s new Pandemic Sciences Centre, giving it the capacity for rapid decision-making and intervention on the world stage.

Commitment to collaboration

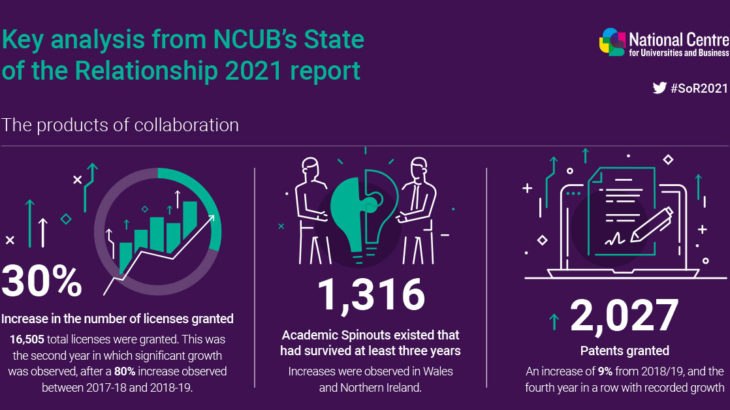

The Collaboration Progress Monitor uses 25 different metrics, such as how many patents have been granted over a year, to help examine annual changes and track long-term trends. The aim is to show whether the UK is on track to grow collaboration year-on-year. Due to the disruption of the pandemic, the latest year in which most data was available is 2019/20, so this was analysed and compared to a five-year average.

The number of licenses granted by UK universities has grown (30%), as has the number of patents granted (9%). There’s also been a huge increase in students starting degree apprenticeships – up 114% from 2017/18. This demonstrates the strong commitment universities have to post-research translation, even in the challenging context of the last few years.

Tomas Coates–Ulrichsen, director of the university commercialisation and innovation policy evidence unit at the University of Cambridge, believes that universities have the potential not just to lead transformational projects but also to help drive efficiency and productivity in a collaborative state with business. He says: “Through their research, universities contribute to innovation well beyond driving technological advances. Their basic, inspired and applied research, and their varied knowledge-exchange activities with partners can lead to ground-breaking innovations.”

Trends in innovation and collaboration

Moving into 2022, the government has put forward its innovation strategy, with a significant emphasis on enabling the commercialisation of ideas from the UK’s world-leading research base. The October 2021 Spending Review supported this, with research and innovation set to receive an important boost in funding – total public spending will reach £20bn by 2024/25 and £22bn by 2025/26. The NCUB report identifies several trends for the new year that potentially support the strategy.

The first trend is around the rise of innovation districts. The NCUB report observed that despite the rise of online collaboration during the pandemic, geographical proximity remains crucial. This is supported by the innovation strategy, which states: “we need to ensure more places in the UK host world-leading and globally connected innovation clusters, creating more jobs, growth and productivity in those areas”. As a result of the trends noted in the NCUB report, we’re already seeing the emergence of urban “innovation places” that aim to drive inclusive growth across the country.

The government’s R&D people and culture strategy makes clear that building R&D talent must be a focus for universities, businesses and policymakers, to create a culture of collaboration and mobility between academia and industry. This links in with the second trend identified, which is universities making a commitment to new, collaborative initiatives to build a more diverse research workforce. A number of different national and institutional programmes are already starting to embrace this concept within their working practises.

Finally, the report recognised a third trend which is about the growth of wider collaborative university commercialisation activities. This reflects the important role universities play in supporting “spin-ins” and other new business structures.